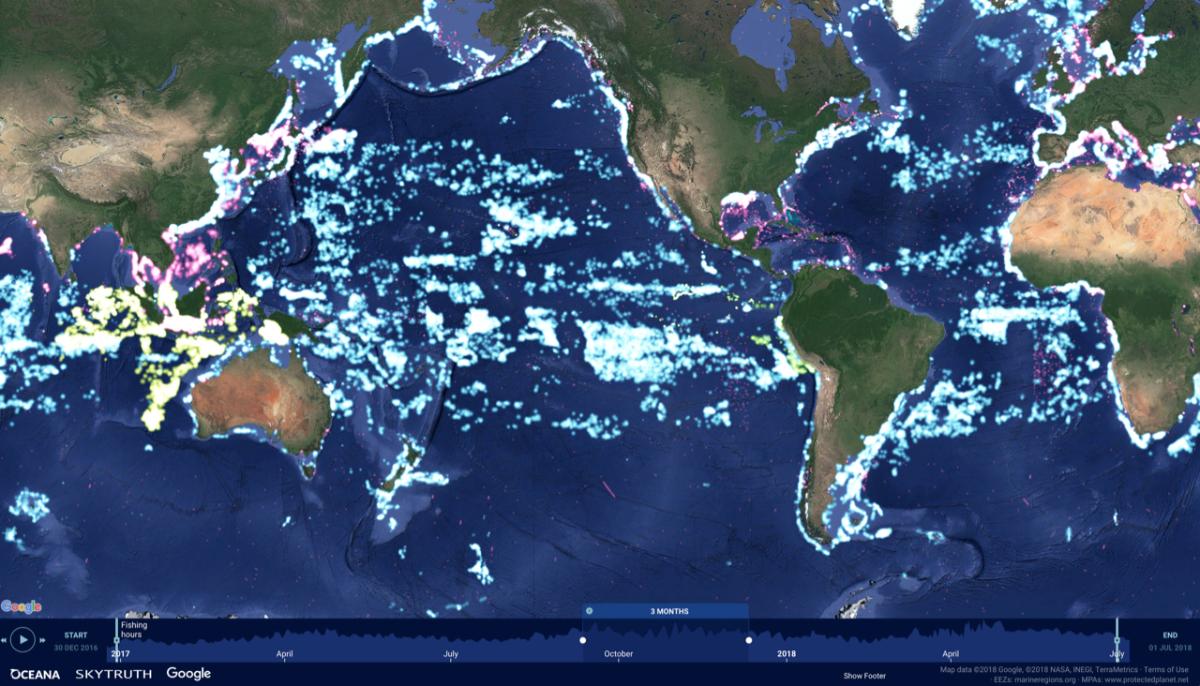

An international nonprofit with the goal of increasing ocean sustainability, Global Fishing Watch has bundled big data, artificial intelligence and satellite imagery to track commercial fishing vessels and reveal potentially illegal operators.

In March, Panama became the latest nation to commit to making its proprietary vessel-tracking data publicly available through the Global Fishing Watch map platform, which provides an unprecedented view of fishing activity on the world’s oceans.

“Panama believes that promoting transparency in fishing management is a key tool to fight illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, improve surveillance and fisheries sustainability, and increase economic and conservation benefits for people and fishing communities,” says Zuleika Pinzón, general manager of Panama’s Aquatic Resources Authority.

Fishy activities surface

Founded in 2015 through a collaboration with Oceana, Google and SkyTruth, Global Fishing Watch (GFW) tracks approximately 65,000 industrial fishing vessels worldwide. Anyone with an internet connection can visit the international mapping platform to track fishing activity in almost real time (a three-day delay) and going back to 2012.

Since GFW’s launch, governments, researchers, conservation groups and others have gathered mapping data to check out suspicious fishing and transshipment activities and create or expand marine reserves, according to Bjorn Bergman, GFW regional manager for Central and South America.

See also: Innovative new apps help Brazil's economy rebound

Off the Peruvian coast, for example, GFW tracked a Chinese vessel’s route for several months in 2018, flagging the ship when it crossed into Peruvian waters without authorization, according to GFW and Peruvian representatives. Authorities intercepted the vessel and found 19 tons of squid, which they suspected had been illegally gathered inside Peru’s exclusive economic zone, which extends 200 miles from its coast.

“If a government suspects a vessel has been fishing illegally in their waters, they can go on our site, pick up the tracking data and make their own decisions,” says Bergman, “Enforcement is up to the country, but the information from GFW can be used as a tool.”

Deploying the GFW platform for another purpose, Mexico recently announced plans to substantially expand the protected area surrounding its Revillagigedo Archipelago (aka Socorro Islands), a UNESCO World Heritage site that thrives with an array of marine life. GFW data helped debunk arguments against the expansion from the tuna-fishing industry, which overstated its operations in the zone, about 240 miles southwest of Baja California.

60 million data points

The GFW platform combines several data sources, amounting to some 60 million points of information daily, to track vessel activity. At the core are:

- • Automatic Identification System data, which roughly 300,000 ships constantly broadcast as a safety measure to avoid collisions, and

- • Vessel Monitoring System data, proprietary information that most fishing nations collect on ships in their waters but had not made public prior to GFW.

Applying machine learning to the data, GFW identifies 12 types of vessels, isolating fishing ships based on their movements and determining the collection methods they use.

“Trawlers, longline and purse-seine vessels all move in different ways. It takes some complicated modelling to make it accurate,” Bergman explained. “There’s a huge diversity of fishing.”

Among vessels GFW identifies are refrigerator ships, which pair up with fishing vessels to transfer the catch, opening another window to suspect activities.

Lighting up ‘dark targets’

Casting a wider net, GFW also taps into NOAA weather satellites (the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite), which are so sensitive that they pick up brightly lighted vessels — most notably squid-harvesting ships that use super-bright spotlights to lure the catch closer to the surface. Satellite radar provides additional, Google Earth-style data for the mapping platform.

See also: Undersea robot designed to vacuum up invasive lionfish

“We know countries are often trying to control waters extending 200 miles from their coast, so these various methods of monitoring ‘dark targets’ that may not be broadcasting their information are really critical,” Bergman said.

Because the information is free and readily available online, it’s useful to a range of interests, such as government agencies, environmental organizations, researchers, journalists and industry groups, according to GFW.

“We’re getting a lot of great feedback,” Bergman said. “We’re working with universities and government organizations around the world, not only in using the mapping data but also helping us with data analysis and improving the final product.”

In 2017, Indonesia became the first nation to provide its Vessel Monitoring System data for GFW’s fishing activity map, making nearly 5,000 previously “invisible” fishing vessels publicly viewable. Peru followed in late 2018; Panama and Costa Rica have committed to begin sharing their data in 2019; and others are likely to participate soon.

"Together, with forward-thinking governments like these, we can bring greater transparency to the oceans,” said Jacqueline Savitz, Oceana vice president. “By publishing fishing data, governments and citizens can unite to help combat illegal fishing worldwide. With more eyes on the ocean, there are fewer places for illegal fishers to hide.”

###

We welcome the re-use, republication, and distribution of "The Network" content. Please credit us with the following information: Used with the permission of http://thenetwork.cisco.com/.