Big success stories can have humble beginnings.

Case in point? Cisco.

Today’s networking, security, AI, and services giant began life in 1984, in the home of Stanford University graduates Len Bosack and Sandy Lerner. Soon after, they hired someone to answer the phones before persuading Kirk Lougheed, another Stanford grad, to come on board.

Lougheed’s been with the company ever since.

In a nearly 40-year career, he’s played a key role in many networking breakthroughs and today is a Cisco fellow and emeritus advisor who continues to support new technologies while mentoring younger engineers.

In a far-ranging interview, Kirk shared his insights on Cisco’s past, present, and innovative future.

Thank you, Kirk! Maybe we could start with your early life. Did you always know you’d work in technology?

I grew up on a wheat farm in northwestern Minnesota. My dad didn’t want any of his kids following in those particular footsteps. But working in technology wasn’t really on the map when I went off to Stanford to study physics.

This was the 1970s, a pretty cool time to be at Stanford.

Yes, I eventually did get a degree in physics, but I came across my first computer when I was 19. There were no PCs then; the computers at Stanford would fill up a room. And I got drawn into the culture of people around them. That led to a job at Stanford’s student computer group after I graduated. At that time, new networking technologies such as 10- megabit-per-second Ethernet were beginning to appear as well as new software protocols such as TCP/IP. It looked like an interesting area to explore, so I basically started specializing in the network stack.

That led to becoming employee No. 4 at a tiny startup called Cisco.

Yes, at Stanford I took over the maintenance and development of the software that eventually controlled Cisco's first router. On the Stanford campus there were different departments that wanted their computers to communicate with one another. So, you could either hook up one long cable, which didn't scale very well, or you could invent something called a router that you could plug different cables into and extend the network in a mesh across the campus.

Were commercial applications being considered then?

Len Bosack was the one that figured out that there might actually be a market for this sort of technology. Other universities started to ask, “Can we have one of those routers, too?” Then in 1980, we showed some prototype units to Hewlett Packard Labs. Their reaction was, “This is great, can we get more of these?” So, it was clear there was a demand. Len and Sandy incorporated the company in December of 1984. But we really didn’t get off the ground until ’86.

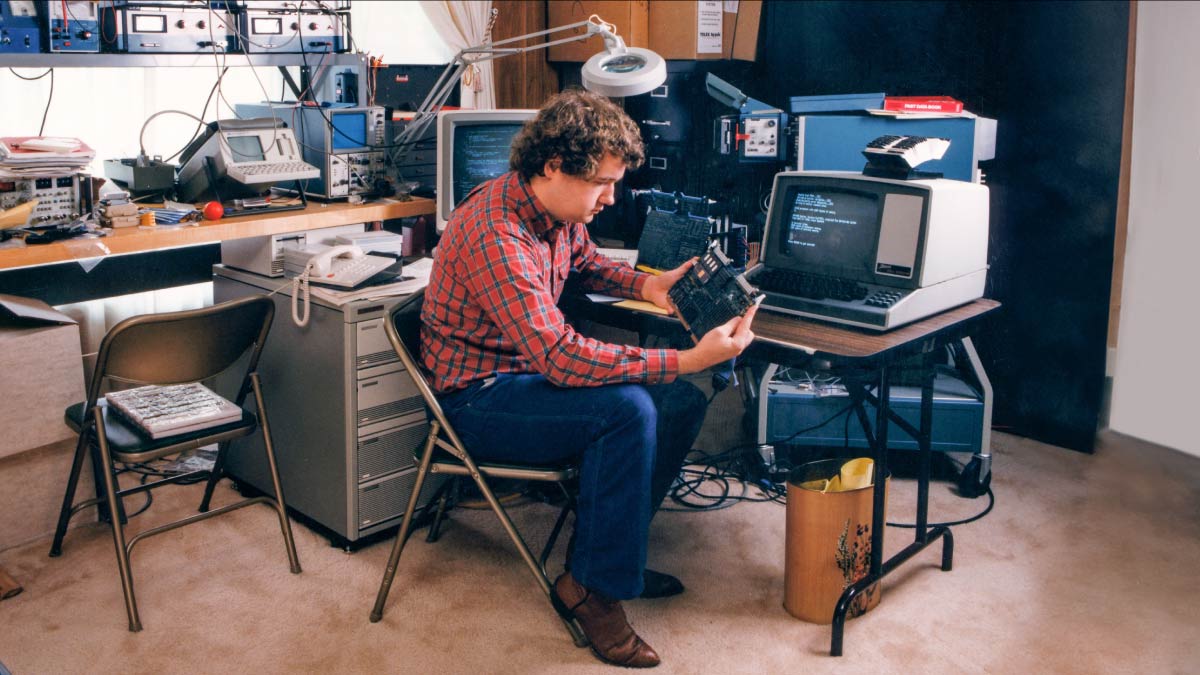

Could you share a snapshot of a day as Cisco employee No. 4?

My first day at work was at Len and Sandy's house — a really nice house in Atherton, California. They had already hired an admin, somebody to answer the phones and work with the vendors and whatnot, Cecilia Strickland.

So, in addition to all those other innovations, Len and Sandy pioneered the concept of working from home?

[Laughs]. Well, the modem speeds were pretty wretched, so not quite like working from home today. We used a couple of spare bedrooms for an office and a lab. When we started assembling routers for sale we took over the living room where Sandy had recently installed some lovely white wool carpet. I still remember Sandy’s reaction to the ugly avocado-green sheets from college that I had laid over her white carpet to protect it. It certainly wasn’t the fashion statement she had in mind.

It must have been an exciting time though.

It was. When the opportunity came, I just jumped at it. It was like doing a high-wire act without a net. You had to pay close attention to selling the routers and listening seriously to the suggestions customers made about the functionality they wanted. If you succeeded, you could meet payroll at the end of the month and buy parts to manufacture more routers. It could be stressful, but it was also fulfilling to see the company grow.

What sort of suggestions were those first customers making?

One of the things we realized early was that our customers wanted to build very large TCP/IP networks. We understood how to scale the technology and used that as one of our selling points. But to make it real we had to invent a routing protocol to do the heavy lifting.

Did that become an early differentiator?

Yes, it was called IGRP, Interior Gateway Routing Protocol, and it enabled people to use routing in their large networks. It worked just fine, but we didn't go through any standards process to create it. Customers didn't really care; they just wanted results. So, while some of our competitors were waiting for the standardized protocol to show up, we were eating their market share.

When did you begin to think that this living-room startup might get really big?

It happened fast. Large enterprises started showing up, and we realized there was serious demand in the marketplace. We knew we needed to get venture capital. And I was extremely relieved when Len and Sandy accepted money from Sequoia Capital. That allowed us to bring in people who knew how to run companies, knew how to do manufacturing, sales, a whole bunch of things that we had no idea how to do. And it pretty much snowballed. We hit the market at just the right time, and we made good decisions about what products to build. We weren't perfect, but we didn't have any fatal screwups. And we were not afraid of acquisitions if we missed some piece of technology that we needed.

You've had a very distinguished career. What are some accomplishments of which you are most proud?

Well, I’m very proud of my role in getting the company off the ground. And I’ve had my hand in many pieces of technology. But probably the one that'll last a lot longer than me is something called BGP, the Border Gateway Protocol. This was 1989, and existing global routing protocol only had room for about 1,000 networks and could handle only relatively simple topologies. It was a cliff we were about to go over. But my co-designer Yakov Rekhter and I sketched out our solution on three napkins over lunch. BGP came out later that year, and it's still the core of the global internet.

That’s amazing. So, you probably get asked this a lot. What kept you at Cisco all these years?

Maybe I just never figured out where the door was. But seriously, there's a lot of people here that I really like and respect. And we have a really good leadership team. Cisco as a company has always had a real honest mission. We're selling technology to solve real problems for people, companies, and the world. Also, the founding group of Cisco was a bunch of computer support people from Stanford, not academics. So, we’ve always been customer driven. It’s deeply rooted. We talk to customers and listen to their challenges. And we’ll move heaven and earth to solve a problem. You do that and you get grateful, loyal customers.

You’re clearly good at seeing around corners. Have any tech developments caught you by surprise?

I would say the rise of the smartphone. Everybody's got a Star Trek communicator with them all the time, all across the planet. That just happened so fast.

Technology’s a double-edged sword. What excites you about the future — or perhaps scares you?

I don’t get scared about technology per se. It’s how people use it that makes me nervous. What does scare me is climate change. We can't decarbonize our infrastructure fast enough, and we're going to need every tool possible to do that. AI, for example, could be very useful: to figure out patterns and better control complicated systems that are creating the carbon. AI is at the peak of the hype cycle right now, especially with large language models. But we are learning to use the technology in important areas, like biomedical research, materials science, and a lot more. But every time you develop a useful tool like AI, malicious actors can find other uses for it. We never saw that coming with the internet; we must guard against it with AI. I’m happy Cisco’s doing some very good work promoting responsible AI.

What’s next for you? Any new challenges you’d like to meet?

Well, I really enjoy my mentoring role. And I’m always interested in seeing what Cisco comes up with next, especially as networks evolve with AI and, looking ahead, quantum. At Cisco, I still get to see it unfold first-hand. There will always be a need to move huge amounts of information around. And Cisco’s exceptionally good at that. So, I’m as excited as ever to see where it all goes.